Author: Nathaniel Slattery

Posted: Month of the Sacred Heart, 1st Day, Year of Our Lord 2023

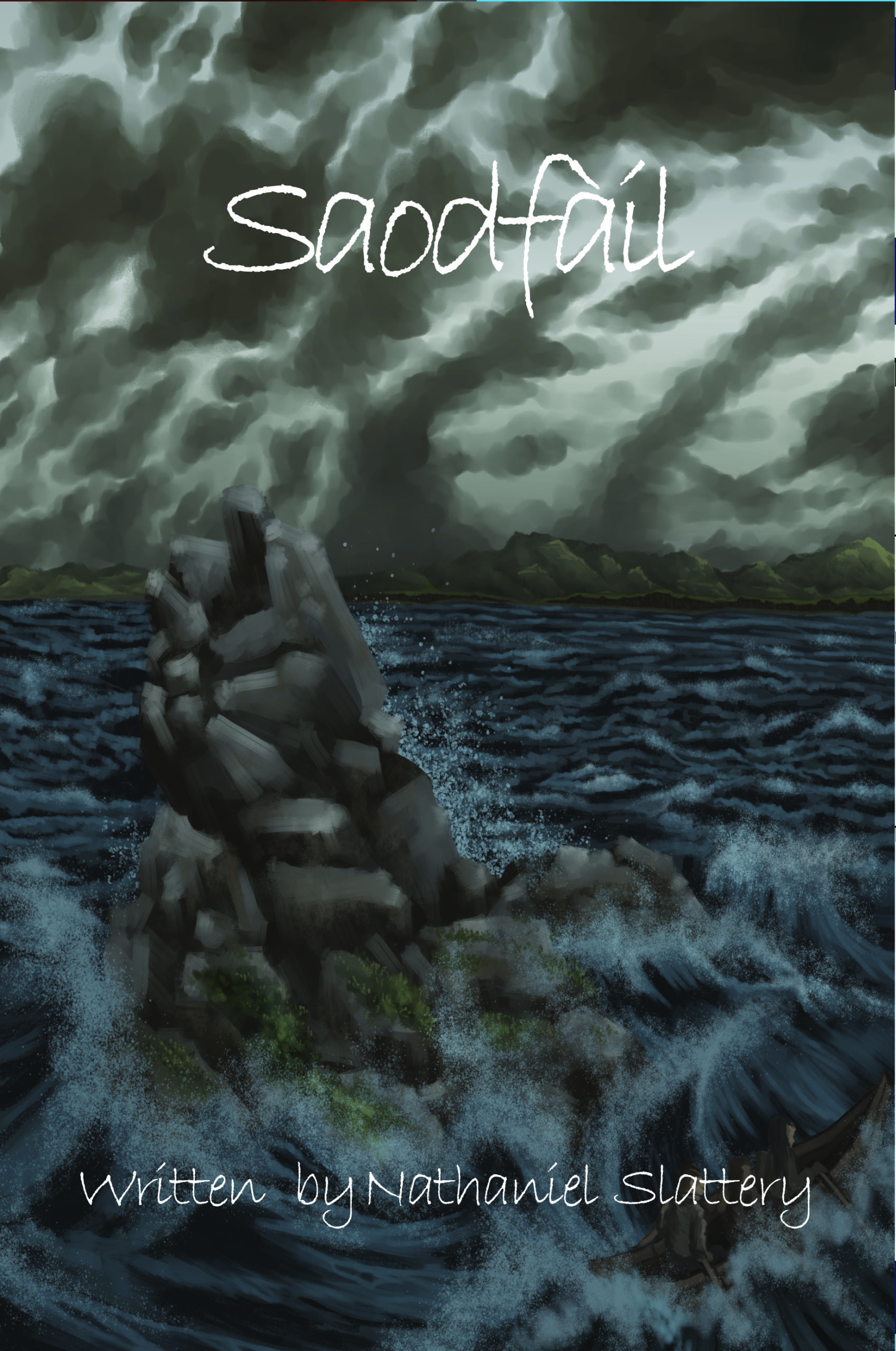

This is an excerpt from a book I have written that is published and available from TaurusNecrus.com. It is called Saodfàil and is a story set in St. Patrick’s Ireland before its conversion. It follows seven characters as they make a pilgrimage to see the High Druid, and is made up in the most part of their telling their stories around the fire at night during each day of the journey. This is the third tale, which is called A Thing Sought.

There comes a place on the road to the place of the druids where the high country falls from the back of a weary traveler like moss scraped from a rock, and two hillsides fall away, one to the left and one to the right, and the world opens up in a verdant swathe. Grass ripples to the breeze of the lower hills, the sun lights the glens like a sea, and all the world is a great and perfect meadow.

In this wolfless and harlotless place, the travelers found themselves on the third day. It was quite brown in the winter, but no snowpile as at Connor’s home. Every one of them felt a new sense of hope and destiny, and some wanted to sing.

Oisin the bard played three little notes on his pipe, the most musical thing he had done in a while, and said to the skies, “Ah, it reminds me of the hills of Judah!”

“Where is that?” asked the woman.

Oisin threw out his hands. He let out a great shout. Three birds wheeled in the sky. “Iberia, the land of horse-bound hermits!”

“You have traveled there?” Acco asked in surprise.

“The lion-runs of Parthia!” Oisin said yet more grandly.

“Madman,” muttered Uilliam.

Oisin shot him an evil eye, and the warrior flinched in fear at the little, fat man.

Drawing down, his arms returning to his chest like the wings of a hen, his face sinking and then falling, his eyes resting apathetically on the horizon, he finally said, voice as subdued now as his posture, and yet still loud and aware of its audience, “But it is only home, the place of my father, and his father, and lo does this heart wallow in bored resignation.”

Connor glanced backwards at the bard, as did Padraig from the front. Padraig’s boy, bouncing along with the rolling of the wagon, said quite innocently, “When will we hear a story, Master Bard?”

Like a chick from under a hen’s bosom, Oisin smirked. “Soon, boy,” he said.

That night they camped upon the meadow. All the travelers knew that the bard was building his heat, and they all were quite asway with the promise of rhyme and a sailing far afield with a tale, as only men of the Eireann ever could be.

“It occurs to me,” began Oisin, and everyone tensed with great anxiety, “that two foreigners have told their small and dusty tales, with no flourish, no skill, and, above all, no showmanship.”

“Lo!” said the woman who clapped.

“And I, a bard, a poet, a skall, a wandering tale-teller and ne’er do well, singer and maestro, who has seen quite a bit more of Europa than this fisherman or of the Otherworld than this brute,” this with a wink and a nod at the two, Uilliam playing along well, but Acco looking scandalized, “and I have yet to tell even a single tale!”

“Right!” said Padraig’s boy, “Come tell us!”

“Aha, my precocious urchin,” said Oisin, “First I must exact my price, or I shall be like the one-eyed cat!”

Connor, who knew that tale, said, “What is your price?”

“We have heard some, but not every, and I demand you four remaining to tell me with glee your tales, so that we may rest complete.”

Connor’s heart sank. Cronan was quiet as he had been a long time, but the woman nodded, and Padraig shrugged.

“And I shall choose the order, and we shall not deviate!”

“We agree,” the woman said.

Oisin considered her. He said then, “Padraig, Cronan, Aletta, Connor.”

Connor smiled, for there was only three days left of travel.

Oisin grinned toothily, blew once on his pipe, and began:

It snowed in Tara the year I left.

This may seem but a mundane thing to you mighty men, heroes of antiquity, but I tell you that there exists in the settlement on the river near Tara, in the Black Pool, something for which in all the world I searched in vain, not indeed at first, for I took it as the normal state of affairs, but after suddenly noticing its lack, I did desperately, as one searches for home in a rainstorm.

This thing was the democratic equality of man. It was a monastery not far from the Druidic circle, location chosen not by convenience but expedient deliberation, for one converts the other in its momentum, but the other corrupts the one by the slowing thereof. So the contest is on! But in all the world it is either ended or not yet begun.

Do I surprise you? Do my words accost you? Is our monk-reject, fisherman friend most surprised? Do not be, for I have read and written such vast treasure-houses of word and symbol such that the storehouses of Egypt, were they filled with them, would have more than seven years supply with which the people could starve.

Now, I say this, the sons of Gael have crossed the timeless world from far east of Parthia to far west of Londinium and have found in all of it no satisfaction for the poetic soul which our Homerian companion names a curse, and such it is, for the sacking of Rome which Gael did in his cradle should be the crowning event in this very epoch where we speak now. But we found it and stole it and left it, and we found the thing which a son of Eire, that youngest daughter bereft of the choice suitor, always desires. This is home. This is our island. Eireann. A more ancient name is the Isle of Destiny, Inisfàil, and how could justice be more poetic?

Now we are a backwater. What new surprise! Oh, but Acco’s people, the Roman truly as the Gaul does not know him, they find only our mud and our dogs, and they understand not our poems, and they say to themselves, “How can a people be so primitive as to live in mud? Have they learned not the cutting of stone?” Oh, but they forget how well we have learned it. They remember not that we pulled the careful stones of Rome one block from another, and found the mortar quite unsatisfying. They forget, too, their myopia which said upon a land, “How can a people’s King be so pitiful as to say nothing against His condemnation by His Own people? I wash my hands of it.” And they return to their great Emperor who by the blood of martyrs is now a Christian.

Let me surprise the warrior as I do the monk. The Christian shortly wins. Even now, I prophesy, that a man is prepared for the conversion of our great isle as yeast is prepared for a cake. A little heat, and it shall be over. So let our Pict or Scot, our Alban, pick the mightier side as they always will, while we poets wallow in something both higher and lower than victory.

So the snow fell. Like a white blanket, it purified the world quite democratically. Everywhere, from the mighty man’s lodge to the peasant’s cottage, all was unbroken white.

The first was the deer. It laid its tracks and broke this charge. Next, the rabbit, then the dog, then the father who has the lowest store of food for his children and finds it difficult to reconcile “Worry not” with “Provide for the members of thy own household”, until he is out in bad weather.

But I was not a father. No, I was a young man, seeking a thing I did not know was buried in my native soil, and I sailed away to Angelaland.

I was a young and sordid man then, understanding nothing, and yet I was closer to what I would ever seek than ever again I would be. For there was a woman on the boat. She often stood at the bow where the bouncing was by feel not so hard as by sight. Her face was smooth and dark. Her hair was black or brown or red or gold, I do not remember, for I only saw her in the night, but her eyes were green. They glowed with the glow of fickle moon stolen or taken by right from the ninth gateway in the heavens, brighter than night and still darker than day, giving a feeling of an eclipsed sun, pale, unfulfilled, and melancholic.

“Do you think we should make it to Llyn Dain safely?” she would ask me.

“Let me sing another song,” I would say.

I sang often in those days, for I had not learned the subtle art of lying to a woman. So I sang to her of crystal skies and emerald plains, of sapphire seas and diamond shores, of ruby sunsets and onyx evenings. Her eyes would melt, and her melancholy became joy. What is the magic of a Druid to that of a woman? She preferred the truest joys and the truest sorrows, since both are not found in the world, populated by the shadows crafted by the efforts of men to calm their women.

I could have had her then. Irony it is that I sought adventure, thinking I would find enlightenment. I said farewell to her on Roman docks, and I never saw her again.

It rained in Londinium the month I left.

The glistening pavement of cut stone, withstanding the march of a hundred thousand hob-nobbed feet, blood of criminals but not warriors lubricating it, and replaced by those same legions which wore it down, it shined like armor.

The roofs of thatch let out a murmur at the coming of rain which bewitches in a way quite distinct from the pattering of slate or the drum of wood. The Angles were a thickened breed by this, leaving fair Dain’s Mark and Germania to come to such a non-island of fog and downpour. A poet’s soul is drowned there. The thoughtful die young by their own hand.

And so I set out, eschewing the Britons or the Picts or the Scots for something further from Gael’s destiny. I retraced the steps of that great, war-like pilgrimage of a people so distinct and imperial, so profiteering and simple, so complex and tragic, as to be brought in for the succor of Briton-Roman against our blueskin Alban friends. I found the race mysterious as one does an empty nut of the Mediterranean. The morsels hidden in the Briton and the Pict did not interest my starving soul. No, I went after that nut which was so clearly empty from a distance, yet I broke it open and was surprised to find it empty.

And so I came to Germania.

You see, for I am more foreigner than the Alban or the Gaul. I am a complex simpleton and a simple intellectual. I am a joke of the Christian God upon the pagans and the wild spirits upon civilization.

I saw in Germania how the Christian God conquers. I saw the remains of that great oak rendered into Church, and the relics of the saint-lumberjack venerated therein. What a tree that is! What an irony I am!, to be on a Druid’s journey to see an oak speak when I have witnessed the death of the oak’s father. What can it say to me? What can a son say to his father’s murderer? Or executioner. For it was an ax which felled the tree, and I carry only six little pipes, and I am beyond both death and life, for I am irony itself. I am poetry.

It was warm in Germania the week I left.

The people there are like flies or maggots upon a rotting tree. They shift and flutter. They were fleeing when I came, and they were fleeing when I left. They have not war there, only chaos, and no one knows who they are fighting for or against. I know that they were coming to Rome, to Gaul that is, and I know that they were in such numbers as to spell the end of that fair place. But what is an end? The land does not end. The flies are not the doom of the root, only a disperser of matter.

The end, I say, is the Christian God. For He is the doom, and He is the judgment. Germania, the Goths, the Alemanni, the Franks, the thousand and one man’s sons who calls himself a king, they are nothing. It is not in doubt that they have their own religions as well as their own thrones, and all is as short and as shallow as that throne, for it does not last one man’s death. But the chaos does. I do not know if the Christian God shall conquer them or simply exterminate them.

But as for I, I traveled to Rome.

I made a resolution upon my heart, a supple, deceiving thing. I said I shall go and see the beginnings of all this. How wrong I was, for I rather saw the end, but the beginnings were there as well.

I shall spare you all the harrowing encounters I had with bandits and wolves in that most civilized of journeys upon endless roads that end in Rome. One would think we live in a pacified region, this backwater! Suffice it to say, I was ripped from my ponderous cloud and sent in a jarring descent to dirt.

I arrived in Rome destitute. This would not have been a problem, for the thing I sought was nearer the brothels and the work-pits than the manors and the suburbs, except that I gaped in the streets.

It was stonework at which I gaped. Here was something I could not find elsewhere, only the limits of a thing like the echo of a shout far-off, but here was a city eternal, a place built by masons. I saw statues of men as tall and imposing as the oaks. I saw blocks of paving as shapely as the body. I saw sewers as well-cut as nothing in nature so much as natural-hewn caverns! Here was the challenge to God which God had conquered! Here was the tower to heaven where all men spoke Latin!

This was how I was found. A publican found me, a Senator, and said, “Are you a Celt?”

I responded in my best Latin, “Are you a Jew?”

The man brightened. “You must be a bard! I have heard of your type.”

“To hear is one thing,” I said shallowly, “to see, another.”

It was not long before I found myself in the Amphitheater. The space between the street and the Amphitheater is something of a dream to me, for I felt ever afterwards that I had lost my mind as well as my path.

I remember one day saying to my benefactor, the Senator, “There are so many people here.”

“Yes, as deserve to listen to you!”

“But what shall I say?”

“You have prepared for months.”

“What I have to say will be heard only by an audience of seven.”

“Then say something else!”

“I must say this thing. The gods have given it to me.”

“Dress it up!”

“What?”

“Put clothes on it like I have on you!”

The Senator had had clothes made for me by the most exquisite tailors in Rome. In all things, they made it Celtic. What I wore when I stood on the street as a destitute son of Gael they rejected, calling it drab and earthly. Instead, I was in gay colors as the birds of hot Malta, a green brighter than grass and a brown more crisp than soil, made by velvet and costly dyes.

I at once took his meaning full to heart. I went before the Romans and told them a story of a warrior from far Eireann who once jumped over a shark. No matter that he had no family, for he loved many women and had many children. No matter that he had no occupation, because he labored without bread or sleep. No matter that he never looked upon a snowy field and ruminated death, as only a son of Eire can, because this was too much for the people of Rome.

I gave those masons many surprises in story and reverse, and gradually murdered the very essence of story. In my heart, I first concealed things and then dispelled them. The fanciful warred upon the conservative such that I thought the rebel was the master, but it soon starved.

Like my plaster and mortar heroes, I loved many women. Like them, I traveled to far Parthia and Iberia, both by horse and by the scrolls in the great scriptoriums. Where Crassus was slain and where Sertorius was murdered, five hundred years later, there I found only the stone hovels of the Romans. Why? Why? Why? My soul burned. Nowhere in all the world which was free to me as an innocent virgin to the bridegroom, could I find that true thing for which I had sought.

I grew mad with frenzy. I began to think that there were greater things denied to me. What of the Senator’s life? Perhaps in the Senate I may find the illusive thing. I had entertained them. I had dined with them.

Their tables were full of the richest foods that had no taste. Their talk pummeled my senses like their food. Law! War! Marriage! Land! Legions! Armament! Craft! Guilds! Church!

All the high devotions reduced to a scribe’s marks on choice Egyptian papyrus. I had skipped right over what mean men found worthy in life. I had found the bare, windswept, desolate pinnacle and left over the climb.

I went to church then. There were many in Rome, reclaimed from their gods by the hand of an Emperor-saint who hailed from Angelaland, though time had had a reverse or two by pagans and heretics. By the time I found myself in Rome, the churches were entirely occupied by the men who call a carpenter God, and yet still build everything out of stone.

So be it. God died upon wood, but He rose from behind a rock tomb. I traveled now, the world still open to me but won and known, to this Man’s homeland. I profess that I had never seen a place so ordinary. The hills were smooth, yes, but they were browner than those of our home. The great city upon a mountain was not suitable for an aqueduct and so like here in Eireann, women carry water in buckets upon their heads from wells, and they are much less comely there. There is nothing to be added to the city, it is already full of staircases and dust. Outside the city, the little villages are ordinary and succumbing to the ordinary encroach of the great Roman mechanism. Bethlehem itself is not far from a Roman outpost where God’s foster father, and likely God Himself, sold furniture crafted by His Own hands.

What was I missing? All the world was upset by such an ordinary Man in an ordinary place, our dear Eireann sure to soon be under the same fateful conversion. For one day, surely, we shall awake and find ourselves Roman Catholic.

But Rome’s churches were in keeping with the grandeur and pomp of a kingdom come. Perhaps that is it. The people of that region, Palestine, have a tale which I memorized of a man named Gideon turning the limitless conquerors inside out with a bare three hundred-man army. Such is the same. Judah conquers Rome not by arms but by theology. Stonework bends to the ageless blood of a Carpenter dying upon wood.

If I have a son, I shall name him Gideon, I decided, and then I decided to go home.

It was dry in Rome the day that I left.

That swampy place. I had sucked it dry myself, the spider of spiders. For the city is like an insect, caught in a web, and it is like the predator, draining the world of fluids. But me, I am a poet, and all the grandeur, all the pomp, all the art, all the ambition of such a place was for me only a liquid diet, and I let my pen flow, and in everything I produced a heap of nothing, of only air, that I imagine never will be read again.

It is better that way. Few people can read letters, and fewer people do, and it is all the wrong ones.

In all my travels I found many things, the answers to all the surmounting questions, but I had skipped over what I sought.

I remember the day I realized this. I was in the Amphitheater which once had granted me fame and the many things which those with simpler hearts desire. My Senator was long dead, but I was known everywhere that Rome’s great families wandered. They knew me as the Bard. I could wear whatever costume fancied me. I had learned and performed many tales of the Christians and their subjects’ old gods.

This day, I performed for Christians. It was the tale of St. Narcissus of Jerusalem. He that was in the rebuilt city, he that rebuilt Passover so as to repudiate the Jews, he that turned water into oil, and he with the name. What a name!

In the crowd, there was a young and handsome officer of the patrician class, and beside him, was the woman. Was she my woman from those many years ago aboard the boat to Londinium? I do not think so. She was young and fresh, but she was of my homeland, and the Roman who held her hand in marriage was not.

I resolved to seduce her. After the performance, I sought her out, and it was an easy matter to separate her from her husband. But even after we were alone, she refused every advance of mine.

“There is no fear of discovery,” I assured her.

She looked aghast at me. “God would know,” she told me.

This is something for a long time I have pondered, perhaps as long as our dear Alban companion ponders whether to slay this or that foreigner. I can say that I learned something of the carpenter God here which I had missed in His homeland. There is no magic there as there was none in that daughter of Eire’s chastity. It is something closer to the grain of life which cannot be cut or altered by any power, but must be worked around.

I did not reach this conclusion immediately. Rather, I loved many lesser women and did what many a man does for pleasure, and I tried to dispel the failure from my heart, which, being a poet’s, refused to relinquish it.

And so, I returned home. For I discovered in my heart a desire to seek out that thing I had flown so high above, namely that wooden grain, which inspired that woman to refuse me.

I had pleasure in Gaul and Angelaland. Not women. I found them displeasing. So, too, the old pursuit of them, founded on subtle deceptions only skin-deep which both parties agree to in order to ignore the obvious nature of it.

Eventually, I came to Eireann. Here, I sought out the house of my father, but he was dead. His klann had moved, I know not where.

On a snowy day, I looked out across the glens and realized I needed a wife, or my father’s line would die out. Of the wives available, I cannot marry a daughter of Eire, for she will subsume my klann. I must find a slave. Of the best slaves, the High Druid has the choicest in beauty and virtue, and many Christian ones.

“So, I expect to purchase one quite fairly. I hope for one that shall show me what I have missed. Eireann, itself, I have always overlooked, and irony finds me cut off from it as surely as I have returned to its traditions and cultures.”

When the bard finished his tale, far from being struck with wonder or amazement except, perhaps, for how very unbardlike the tale had been, his audience shifted uncomfortably. There was a palpable sense of unspoken questioning. “Is that it?” hung in the air as if an angel or demon spoke it.

Connor, particularly, was caught up by how the little, fat man had begun with such grandeur and promise. It had been a comfortable thing, like many tales he had heard. Now it was an uncomfortable thing, a thing with all its unspoken questions and high ponderings that compounded deeply with the general discomfort which had started at the first telling of tales. He knew only one thing from the story. There was no need to fear this bard.

“But what about the Otherworld?” Uilliam asked impatiently.

“What?” Oisin said unpoetically, his tone of the same that had suddenly developed at the onset of his story, no lilting and lyrical lightheartedness.

“You said,” Uilliam explained, “that you had seen more of the Otherworld than I have.”

Oisin’s eyes laughed at the Alban. “It is a place seen as the forms casting shadows upon a cave wall. I have not only seen it but studied it, stared it in the face, and tracked it down through a thousand lands to rend its secrets from it.”

“I do not understand you. Did you encounter Muirgen? Was she offered to you?”

“No, my friend. Rather, I was the Muirgen to tempt the heart of another.”

Uilliam shook his head, paused and stared into his own lap somberly, then shook it again.

“I think I understand him,” Acco said soothingly. “He desires to be like the great poets of Rome.”

Oisin laughed.

Cronan said, “I have heard enough.” He left the circle abruptly.

“Some bard,” the woman said.

Oisin smirked knowingly at Connor, who flushed, unsure what the man was thinking.

Cronan’s departure seemed to break a sort of spell, and the rest of the company slowly ambled away, dissatisfied and in many ways upset.

Connor, who was tending the fire as he had tended the wagon, found himself alone with Oisin looking at him.